STEEL

Steel is the most important engineering material. The hardening of steel is very important.

Lecture Videos

(Unedited footage)

![]() Steel: Part 1 ,

Steel: Part 1 , ![]() Steel: Part 2 ,

Steel: Part 2 , ![]() Steel: Part 3

Steel: Part 3

![]() Properties and Grain Structure: BBC 1973 (Old but very good)

Properties and Grain Structure: BBC 1973 (Old but very good)

Iron is abundant in the universe, found in the sun and many types of stars in considerable quantity. The core of the earth is thought to be made up of nickel and iron, and to be hotter than the Sun's surface. This intense heat from the inner core causes material in the outer core and mantle to move around (convection currents).

(Note: Funny how we don't really know eh? - We know it gets hotter as you dig deeper, but we can only guesstimate how hot it is at the center of the earth. Even at 12km underground the calculations of scientists were out by more than 100% - it was hotter than expected. When trying to drill to these depths, the rock gets so hot that it becomes plastic and squeezes back on the hole and jams the drill. Rats. So much for digging to the centre of the earth.)

Carbon Steel

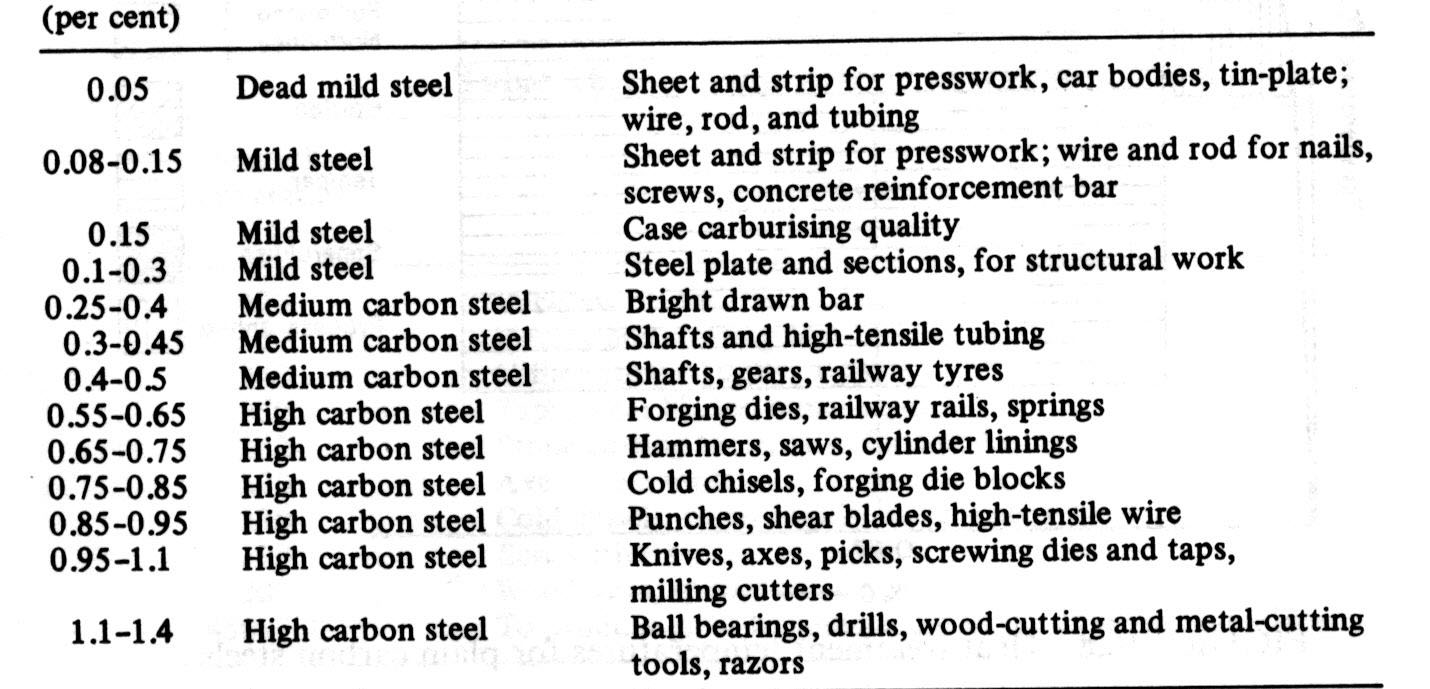

Steel is an alloy of iron (Fe) and carbon (C), with 0.2 to 2.04% carbon by weight. Carbon is the most cost-effective alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten.| Carbon Steel | ANSI def'n | General Def'n | Applications

and properties |

| Low carbon steel | 0.05–0.15% | <0.1% | Soft, ductile. Easy to form. |

| Mild Steel | 0.16-0.29% | 0.1-0.25% | Low tensile strength, but it is cheap and malleable; surface hardness can be increased through carburizing. |

| Medium carbon steel | 0.30–0.59% | 0.25-0.45% | Balances ductility and strength and has good wear resistance; used for large parts, forging and automotive components. |

| High carbon steel | 0.6–0.99% | 0.45-1.0% | Very strong, used for springs and high-strength wires. |

| Ultra-high carbon steel | 1.0–2.0% | 1.0-1.50% (>1.5% rare) |

Very hard - knives, punches. Usually anything over 1.2% would require other alloys to prevent excessive brittleness. Very high carbon content can be achieved using powder metallurgy. |

| Cast Iron | – | 2.5-4.0% | Lower melting point, easy casting, lower toughness and strength than steel. |

Carbon percentages in various steel applications;

Varying the amount of alloying elements and the way they incorporated into the steel (solute elements, precipitated phase) influences such properties as hardness, ductility and tensile strength of the resulting steel. With increased carbon content steel becomes harder and stronger than iron, but also more brittle. The maximum solubility of carbon in iron (in austenite region) is 2.14% by weight, occurring at 1149 °C; higher concentrations of carbon or lower temperatures will produce cementite (very brittle). Add any more carbon and you get cast iron, which has a lower melting point and is easier to cast.

Wrought iron containing only a very small amount of other elements, but contains 1–3% by weight of slag in the form of particles elongated in one direction, giving the iron a characteristic grain. It is more rust-resistant than steel and welds more easily. It is common today to talk about 'the iron and steel industry' as if it were a single entity, but historically they were separate products.

Steel has been produced for thousands of years, but

it became common after more efficient

production methods were devised in the 17th century. The Bessemer

process in the mid 1800's made steel relatively inexpensive

for

mass-produced goods. Further refinements in the

process, such as basic oxygen steelmaking, further lowered the cost of

production while increasing the quality of the metal. Today, steel is

one of the most common materials in the world and is a major component

in buildings, tools, automobiles, and appliances.

Get pdf: XLER_International_Compare.pdf

VIDEO: Properties and Grain Structure. BBC 1973

Don't laugh at the date - this video beats all those pathetic modern ones that give you a fancy intro but nothing more than a talking head. They never venture out of the studio. This old video is fabulous for a clear introduction to steel grain structure.Part 1: What is a grain? (Video 11MB)

- The patches seen on a galvanised object are crystals or grains of zinc.

- All metals are made up of grains, but they are usually invisible (too small to see or same shine/colour).

- Etching Process: Mirror finish, powerful acid, washed and sealed.

- In a pure metal, the grains are different colours because of the way they reflect the light.

- Tiny crystals grow outward until they meet. Each fully grown crystal is called a grain.

- Before cold working the grains are similar size and shape

- Cold working elongates the grains, increases hardness and strength increases, reduces ductility.

- At 350C, new grains form in the Al to replace old grains. Called recrystallisation

- Recrystallisation softens, lowers the strength, ductility increased

- Excessive recrystallisation temp gives poor mechanical properties

- Steel grains are too small to be visible - need a microscope approx 250 times magnification.

- Ferrite: Light coloured. Made of iron. Ductility to the steel

- Pearlite: darker coloured. Layers of Iron + Iron Carbide. Hardess and strength to the steel

- 100% Pearlite is about 0.8%C. Pearlite, recrystallisation temperature 720C.

- Normalising - cooled in air, reduced grain size and more uniform shape, toughness increased

- Quenching - increases hardness. Not enough time for pearlite to form, so a needlelike strcture forms - martensite. Very hard and brittle.

- Tempering - (after quenching) restores toughness. Modifies the martensite needles with small flakes of carbon. This gives hardness AND toughness.

- 0.1%C steel (Mild Steel). Recrystalisation 900C. Not enough carbon to produce martensite.

Iron-Carbon Equilibrium Diagram

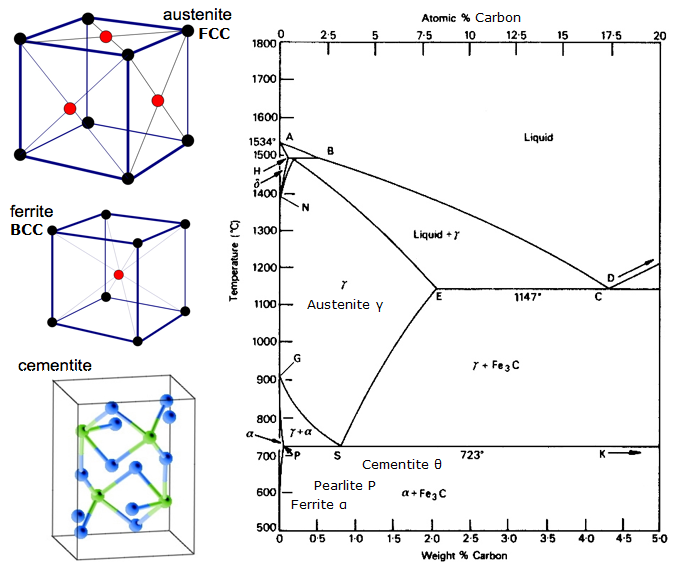

Excellent link (Cambridge University): http://www.msm.cam.ac.uk/phase-trans/2008/Steel_Microstructure/SM.htmlAn Equilibrium diagram is a graph of the different structural arrangments that occur within a range of an alloying element.

This diagram shows how iron and carbon combines IF it is cooled slowly (in equilibrium). Under 2% is steel, over 2% is heading into the cast iron range where carbon tends to coagulate (clump together). Cementite Fe3C has 6.67%C and it is basically a ceramic. The eutectoid (pearlite) at E has 0.83% C, less carbon is a hypoeutectoid steel (A), and greater is hypereutectoid (B). Alpha iron (ferrite), gamma iron (austenite, which only exists at high temperature), and delta iron (another high temp structure).

Two very important phase changes take place at 0.83%C and at 4.3% C. At 0.83%C and 723ºC, the transformation is eutectoid, called pearlite. These 2 phases separate out in layers. From gamma (austenite) --> alpha + Fe3C (cementite)

At 4.3% C and 1130ºC, the transformation is eutectic, called ledeburite. L(liquid) --> gamma (austenite) + Fe3C (cementite). This is cast iron.

BTW. Since carbon (12) is much lighter than Fe (56), the actual atomic % Carbon (by counting atoms) is actually about 4.6 times higher than the %C by weight. So it's not quite so amazing now is it? I mean like how 0.5% Carbon can totally transform soft iron... it's really about 2% if you count atoms - not mass.

Summary of Fe-C structures (grains)

- Austenite (γ-iron). Only exists above 723C, which is when

the FCC γ-iron structure occurs. Can dissolve up to 2.1%C by

mass. Non-magnetic, soft (hence we have hot-working). Austenite can also exist at room temperature if you swap out some Iron atoms for something else - like Nickel. This is what Austenitic stainless steel is - like 316 for example. And, like the high temperature Austenite, these stainless steel are non-magnetic. Some other types of stainless steel are magnetic.

- Cementite (Iron carbide Fe3C, 6.67%C by mass. There are twelve iron atoms and four carbon atoms per unit cell, so 33% carbon atoms). Very hard and brittle because it is a ceramic. Ever heard of Tungsten Carbide? Well, this is Iron Carbide.

- Ledeburite (The Ferrite-Cementite eutectic, 4.3% carbon.)

- Ferrite (α-iron, δ-iron; soft). No carbon, BCC. Soft and ductile.

- Pearlite (88% ferrite, 12% cementite, which is 0.83%C) Stronger then Ferrite

- Martensite. Occurs when cooling is too rapid to form Pearlite, so it locks spikes of Cementite into the grain. This occurs with the quench-hardening of steel with enough Carbon in it. Very hard.

Micrographs (photos from a microscope).

(A) = 0.1%C ferrite/pearlite,

(B) = 0.25%C more pearlite, (C) = 0.83%C all pearlite, (D) = 1.4%C

pearlite/cementite

Close-up view of Pearlite showing layers of ferrite (white) and

cementite (dark).

More about Pearlite: https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_7/backbone/r7_1_2.html

Large FC Equilibrium Diagram

Large Print Version 2000x2658px

Slip

When a piece of metal is deformed, it is the

grains that

are deformed. A grain is a crystal, an orderly arrangement of atoms in

a grid. If atoms are stretched apart this is elastic

deformation

because the atoms are held together by electron attractions - which

acts like a spring. However, permanent (or plastic)

deformation

means the atoms actually slip past each other in layers or planes.

Real crystals do not slip in a whole plane at once. This would take a

very high force. Instead, the imperfections in the crystal allow slip

to travel one atom at a time. The wider the range of effected atoms,

the more ductile (easily slipping) the grain is. Here is an

example of an imperfection called a dislocation which

can travel easily through the crystal.

Here is an actual example of slip. (we are not just making this up!)

A scanning electron micrograph of a single crystal of cadmium deforming

by dislocation slip on 100 planes, forming steps

on the surface.

The following animation shows a lattice of atoms (such as in a metal). There are only 2 ways to distort the atoms - axial (tension and compression) and shear (sideways).

This animation shows only the elastic portion of the stress/strain curve, where no atomic slip occurs.

Further information here: http://www3.nd.edu/~manufact/MPEM_pdf_files/Ch03.pdf

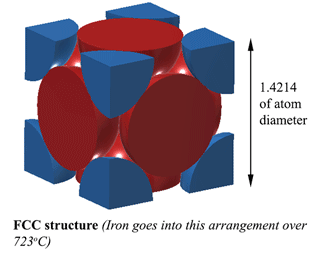

So what is BCC and FCC anyway?

The BCC (Body Centred Cubic) and FCC (Face Centred Cubic) crystal structures are two alternative ways to pack Iron atoms.

- BCC is the room temperature arrangement called Ferrite

- FCC is the high temperature (>723oC) arrangement called Austenite.

Download Inventor files: SC, BCC, FCC, All three (SC+BCC+FCC)

![]()

SC is Simple Cubic and does not occur with Iron atoms. This is the lattice of salt - NaCl.

The smallest arrangment (unit) is shown below. Notice how the cubic grid (coloured blue) is expanding as the other atoms are fitted between them in BCC and FCC lattices.

![]()

There is often some confusion about these diagrams below.

The problem is that the red atoms look like carbon and black atoms look like iron. No, no, no!

Every atom is Iron! We just colour the Iron atoms that are not on the corners to make them easy to see.

The other problem with these diagrams is that there is no real indication that the spacing of the corner atoms INCREASES as you go from SC to BCC to FCC.

SC (Simple Cubic) structure. NOT IRONWith a SC (Simple Cubic) structure (which iron does not do), the distance between the atoms is D. (Where D is the diameter of the atoms) So volume of this unit is D3, and volume of atom is 4/3Πr3. So density is 52% of solid atom. Not very compact. |

|

BCC (Body Centred Cubic) structure. FERRITEWith a BCC (Body Centred Cubic) structure (which iron does under 723oC), the distance between the iron atoms is 1.1547D. (Where D is the diameter of the atoms) So volume of this unit is (1.1547D)3, and this fits 2 atoms so volume of atoms is 2x4/3Πr3. So density is 68% of solid atom. More compact. This structure is called Ferrite. Carbon does not fit into this structure at all (Well, I tell a lie. It can dissolve a pathetic 0.025% C, which is virtually zero, or 0.035% at the transition temperature, which is still nothing) |

|

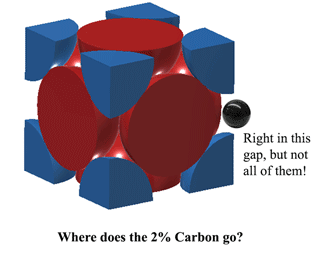

FCC (Face Centred Cubic) structure. AUSTENITEWith a FCC (Face Centred Cubic) structure (which Iron does over 723oC), the distance between the Iron atoms is 1.4214D. (Where D is the diameter of the atoms) So volume of this unit is (1.4214D)3, and this fits 4 atoms so volume of atoms is 4x4/3Πr3. So density is 74% of solid atom. This is the most compact, making it 6% more dense than Ferrite! This structure is called Austenite, and it can dissolve 2% Carbon into its structure. That's 2% by weight don't forget, and since Iron (56) is 4.7 times the weight of Carbon (12), it can dissolve about 21% Carbon atoms (About 1 Carbon for every 5 Iron atoms). |

|

So where does the Carbon fit in Austenite?Carbon can fit right in that space in the middle of each unit edge. However, this causes a bit of distortion, so you cannot fit a Carbon atom on EVERY edge. At very best, at 1130oC Austenite can fit just over 2 Carbon atoms every 3 units. (2C:12Fe or 1:6 by atoms). That is where 2% by weight comes from. More here (pretty heavy) |

|

Further information about BCC and FCC here:

http://lessons.chemistnate.com/simple-cubic-fcc-and-bcc.html

Video of Simple Cubic, Body-Centred Cubic and Face Centred Cubic crystal structures. Iron atoms do not form Simple Cubic.

Simple Cubic, Body-Centred Cubic and Face Centred Cubic

Hardening of Steel

Hardening is all about stopping slip from happening.

There are 3 ways to do this.

- Get rid of all imperfections (pretty impossible task, although this is why very fine fibres can give crazy strengths)

- Use up all the slips so that no more slipping can occur. This is called work-hardening.

- Block slip from travelling all the way through the grains. Carbon (and Nitrogen) form compounds that act as a hardening agent, preventing dislocations in the iron crystal lattice (Ferrite) from sliding past one another. Martensite does this beautifully. This is heat treatment hardening.

Quenching of steel is not shown on the Fe-C equilibrium diagram, because quenching is not in equilibrium! (i.e. cooling is too fast for the Austenite with carbon in it to get itself in the complicated Pearlite structure.

From https://www.tf.uni-kiel.de/matwis/amat/iss/kap_7/backbone/r7_1_2.html

The rapid cooling (quenching) produces a different grain structure called Martensite. This grain is extremely hard and strong, and brittle. The Iron Carbide spikes that penetrate through the grain now prevent slip, so the ductility is lost.

Martensite: University of Cambridge

To reduce the brittleness after quenching, tempering is used to add toughness to the steel. This modifies the dendrites of carbide to give them a bit of ductility - without losing too much strength and hardness.

Tempering must be at a temperature below recrystallisation. An oven is best for tempering, but it can be done by flame by judging the colour of the steel. Temper colours can be used as a guide to temperature. The hotter the tempering, the softer the steel.

Alloys such as

stainless steel form thinner films than do carbon steels for a given

temperature and hence produce a colour lower in the series. For

example, pale straw corresponds to 300°C for SS, instead of

230°C for CS. The colours colder than the reds (below 500°C)

are actually discolouration of oxides, not the actual radiation glow of

the temperature itself. (Which would be infra-red, and invisible. So everything is glowing, you just can't see the light!)

| Radiation Colour | Celcius | Farenht | Tempering Applications / Other |

| Yellow-White | 1539°C | 2800°F | Highest melting point (0%C pure iron) |

| Bright Yellow | 1130°C | 2066°F | Lowest melting point (4%C cast iron) |

| Yellow | 1093°C | 2000°F | Copper melts at 1084°C, Gold 1063°C |

| Dark yellow | 1038°C | 1900°F | |

| Orange yellow | 982°C | 1800°F | |

| Orange | 927°C | 1700°F | Brass melts 930°C |

| Orange red | 871°C | 1600°F | |

| Bright red | 816°C | 1500°F | |

| Red | 760°C | 1400°F | Steel recrystalisation temperature 723°C |

| Medium red | 704°C | 1300°F | |

| Dull red | 649°C | 1200°F | Aluminium melts 600-660°C |

| Slight red | 593°C | 1100°F | Toughening for constructional steels. |

| Very slight red, mostly grey | 538°C | 1000°F | Toughening for constructional steels. |

| Dark grey | 427°C | 0800°F | Toughening for constructional steels. Magnetic change 410 |

| Oxidation Colour | Celcius | Farenht | Tempering Applications |

| Blue | 302°C | 0575°F | Saws for wood, springs |

| Dark Purple | 282°C | 0540°F | Cold chisels, setts for steel |

| Purple | 271°C | 0520°F | Press tools, axes |

| Brown/Purple | 260°C | 0500°F | Punches, cups, snaps, twist drills, reamers |

| Brown | 249°C | 0480°F | Taps, shear blades for metals |

| Dark Straw | 241°C | 0465°F | Milling cutters, drills |

| Light Straw | 229°C | 0445°F | Planing and slotting tools |

| Faint Straw | 199°C | 0390°F |

Quenching:

Speed of quenching: Higher carbon steels can be quenched more slowly, but a lower C steel will need to be rapidly quenched to have any hardening effect.

Quenching Rate: (FASTEST) Salt water > water > oil > air > insulated. (SLOWEST)

For a complex and expensive job, it is better to have a slow quenching alloy because it is less sensitive to variations of temperature. This is why most tool steels for things like injection moulding tools are OIL quenched. Water quenching is fine for simple shapes that can be controlled more easily, but it can cause cracking on thicker sections because the surface shrinks before the inside does.

Induction Hardening. Induction Hardening where electric induction (rapid magnetic changes) heat up the steel which is quickly followed by quenching in water jet. Alternative way of heating instead of flame or oven.

Induction Hardening. http://www.thermobondflame.com/Services.page?i=4

How to harden the surface: CASE Hardening.

Heat treat = quench > Martensite (arrests slip).

Heat outside surface > quench. Local flame or induction quenched with water (gears).

Carbon penetrating the outside surface > quench. Carburizing (Heat up in carbon packing or carbon gas or heated solutions). Nitriding uses nitrogen instead of carbon to have a similar effect, and it is easier to get it to penetrate the surface.

Flame Hardening of steel roll.: http://www.thermobondflame.com/Services.page?i=2

Alloy Steels

Effects of alloying elements on tool steel properties: (Very roughly)- Carbon: Raising carbon content increases hardness slightly and wear resistance considerably. Dramatic increases to hardness & strength when heat treated.

- Manganese: Small amounts of of Manganense reduce brittleness and improve forgeability. Larger amounts of manganese improve hardenability, permit oil quenching (less severe queching required - which reduces quenching deformation).

- Silicon: Improves strength, toughness, and shock resistance.

- Tungsten: Improves "hot hardness" - used in high-speed tool steel. Very dense (heavy)

- Vanadium: Refines carbide structure and improves forgeability, also improving hardness and wear resistance.

- Molybdenum: Improves deep hardening, toughness, and in larger amounts, "hot hardness". Used in high speed tool steel because it's cheaper than tungsten.

- Chromium: Improves hardenability, wear resistance and toughness.

- Nickel: Improves toughness and wear resistance to a lesser degree.

Including these elements in varying combinations can act synergistically, increasing the effects of using them alone. (For example, cetain alloying elements can allow more carbon, where so much carbon would be unworkable in a plain carbon steel). Another example is the interesting way stainless steel (Chrome and Nickel added to Iron) is quite corrosion resistant.

Steels Identification Codes

AISI-SAE Coding system (American Iraon and Steel Institute - Society of Automotive Engineers). A 4 digit code, the first 2 digits give the general steel type, and the last 2 digits are the % Carbon x 100. For example, 1010 is plain carbon srteel with 0.10% C, 5120 is a chromium steel with 0.20% C. More detail here

American Steel codes: From Higgins: Materials for Engineers aand Technicians 5th Ed. 2010. p21

The BSA (British Standards Association) uses a 6 digit code. The digits separated into 3 groups as shown below. For example, a steel with the code 070M20 would be 070 = carbon or carbon-manganese steel, M = mechanical property specification, 20 = carbon content 0.20%.

British Steel codes: From Higgins: Materials for Engineers aand Technicians 5th Ed. 2010. p20

The UNS number (short for "Unified Numbering System for Metals and Alloys") is a systematic scheme in which each metal is designated by a letter followed by five numbers. It is a composition-based system of commercial materials and does not guarantee any performance specifications or exact composition with impurity limits. Other nomenclature systems have been incorporated into the UNS numbering system to minimize confusion. For example, Aluminum 6061 (AA6061) becomes UNS A96061. Below is an overview of the UNS system, with special emphasis on common commercial alloys. As with any system, there are ambiguities such as the distinction between a nickel-based superalloy and a high-nickel stainless steel.

•Axxxxx - Aluminum Alloys

•Cxxxxx - Copper Alloys, including Brass and Bronze

•Fxxxxx - Iron, including Ductile Irons and Cast Irons

•Gxxxxx - Carbon and Alloy Steels

•Hxxxxx - Steels - AISI H Steels

•Jxxxxx - Steels - Cast

•Kxxxxx - Steels, including Maraging, Stainless Steel, HSLA, Iron-Base Superalloys

•L5xxxx - Lead Alloys, including Babbit Alloys and Solder Alloys

•M1xxxx - Magnesium Alloys

•Nxxxxx - Nickel Alloys

•Rxxxxx - Refractory Alloys ◦R03xxx- Molybdenum Alloys ◦R04xxx- Niobium (Columbium) Alloys ◦R05xxx- Tantalum Alloys ◦R3xxxx- Cobalt Alloys ◦R5xxxx- Titanium Alloys ◦R6xxxx- Zirconium Alloys

•Sxxxxx - Stainless Steels, including Precipitation Hardening Stainless Steel and Iron-Based Superalloys

•Txxxxx - Tool Steels

•Zxxxxx - Zinc Alloys

Tool steels

Tool steels are covered in Australian Standard AS1239 and is virtually the same as the American AISI tool steel classification. (Similarly with British Standard 4659)

Steels Selector

Large Size (400kB): steel_types_large.jpg

Printable Size (1.7MB): steel_types_fullsize.jpg

Common steel grades in Australia (Edcon)

Cast Iron

When too much carbon is added to steel, the carbon cannot dissolve into the solution and creates a totally different structure. From the Fe-C diagram we saw earlier, Cast Iron forms in the range of 2% to 7% carbon (by weight).

There are many types of cast iron, but Grey Cast Iron is the most familiar, often used for machine tool bases. It is useful and popular for several reasons.

Firstly, the melting temperature is lower, which makes it easier to cast. This is because the eutectic is at 4.3% C, giving a melting point of only 1147oC. This eutectic produces a new grain called ledeburite, which is a mixture of austenite and cementite. (Remember Pearlite? It was a eutectoid and made of layers of ferrite and cementite). But since a eutectoid is a low point in the liquid-solid transition, it is the melting point.

Secondly, Grey Cast Iron is great for machine bases. Normally, so much carbon would be a nightmare of brittleness due to extreme martensite and cementite. But it turns out that with the right cooling, excess carbon forms flakes of graphite. This is completely different to all these Fe-C grains we've been talking about - like Ferrite and Cementite and Pearlite and Ledeburite. Instead, graphite is like an inclusion in the metal, and it gives Grey Cast Iron the damping properties suitable for machine bases. It is a material with low tensile strength however, so GCI is usually used where it is in compression. GCI is prone to hardening due to excess heat however, so it is not easy to weld. More often it would be brazed, but even that is a bit dodgy compared to the joining of steel.

Photo micrograph of Grey Cast Iron showing graphite flakes in a ferrite matrix. Source

| Name | Nominal composition [% by weight] | Form and condition | Yield strength [ksi (0.2% offset)] | Tensile strength [ksi] | Elongation [% (in 2 inches)] | Hardness [Brinell scale] | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grey cast iron (ASTM A48) | C 3.4, Si 1.8, Mn 0.5 | Cast | — | 50 | 0.5 | 260 | Engine cylinder blocks, flywheels, gears, machine-tool bases |

| White cast iron | C 3.4, Si 0.7, Mn 0.6 | Cast (as cast) | — | 25 | 0 | 450 | Bearing surfaces |

| Malleable iron (ASTM A47) | C 2.5, Si 1.0, Mn 0.55 | Cast (annealed) | 33 | 52 | 12 | 130 | Axle bearings, track wheels, automotive crankshafts |

| Ductile or nodular iron | C 3.4, P 0.1, Mn 0.4, Ni 1.0, Mg 0.06 | Cast | 53 | 70 | 18 | 170 | Gears, camshafts, crankshafts |

| Ni-hard type 2 | C 2.7, Si 0.6, Mn 0.5, Ni 4.5, Cr 2.0 | Sand-cast | — | 55 | — | 550 | High strength applications |

Glossary

- Alloy: A metallic substance that is composed of two or more elements.

- Austenite: Face-centered cubic iron or an iron alloy based on this structure.

- Bainite: The product of the final transformation of austenite decomposition.

- Body-centered: A structure in which every atom is surrounded by eight adjacent atoms, whether the atom is located at a corner or at the center of a unit cell.

- Cementite: The second phase formed when carbon is in excess of the solubility limit.

- Critical point: Point where the densities of liquid and vapor become equal and the interface between the two vanishes. Above this point, only one phase can exist.

- Delta iron: The body-centered cubic phase which results when austenite is no longer the most stable form of iron. Exists between 2802 and 2552 degrees F, has BCC lattice structure and is magnetic.

- Eutectic: A eutectic system occurs when a liquid phase tramsforms directly to a two-phase solid.

- Eutectoid: A eutectoid system occurs when a single-phase solid transforms directly to a two-phase solid.

- Face-centered: A structure in which there is an atom at the corner of each unit cell and one in the center of each face, but no atom in the center of the cube.

- Ferrite: Body-centered cubic iron or an iron alloy based on this structure.

- Fine pearlite:Results from thin lamellae when cooling rates are accelerated and diffusion is limited to shorter distances.

- Hypereutectoid: Hypereutectoid systems exist below the eutectoid temperature.

- Hypoeutectoid: Hypoeutectoid systems exist above the eutectoid temperature.

- Ledeburite: Eutectic of cast iron. It exists when the carbon content is greater than 2 percent. It contains 4.3 percent carbon in combination with iron.

- Liquidus Line: On a binary phase diagram, that line or boundary separating liquid and liquid + solid phase regions. For an alloy, the liquidus temperature is that temperature at which a solid phase first forms under conditions of equilibrium cooling.

- Martensite: An unstable polymorphic phase of iron which forms at temperatures below the eutectoid because the face-centered cubic structure of austenite becomes unstable. It changes spontaneously to a body-centered structure by shearing action, not diffusion.

- Microstructure: Structure of the phases in a material. Can only be seen with an optical or electron mircoscope.

- Pearlite: A lamellar mixture of ferrite and carbide formed by decomposing austenite of eutectoid composition.

- Phase: A homogeneous portion of a system that has uniform physical and chemical characteristics.

- Phase diagram: A graphical representation of the relationships between environmental constraints, composition, and regions of phase stability, ordinarily under conditions of equilibrium.

- Polymorphic: The ability of a solid material to exist in more than one form or crystal structure.

- Quench: To rapidly cool - usually when too fast to form Pearlite, and creating Martensite instead

- Solidus Line: On a phase diagram, the locus of points at which solidification is complete upon equilibrium cooling, or at which melting begins upon equilibrium heating.

- Solubility: The amount of substance that will dissolve in a

given amount of another substance.

DVDs:

Assignment:

Heat Treat

Questions:

Assignment: